In the classical Christian tradition, education is not first about information but formation—of the soul, of the mind, of society, and of the affections. The Quadrivium—the fourfold path of arithmetic, geometry, music (harmonics), and astronomy/cosmology—is one such language through which God’s creation sings His glory.

To understand the Quadrivium, we must first set it within the context of the Seven Liberal Arts. The Trivium—grammar, logic, and rhetoric—trains the mind to hear, speak, reason, and communicate truth. But the Quadrivium takes us further: it leads us into the order and harmony of the universe, as architected and created by the divine Logos. If the Trivium teaches us how to hear and speak truth well, the Quadrivium helps us to behold, measure, and compare truth through number, ratio, and form.

The foundations of this vision were laid by thinkers such as Pythagoras and Plato, who saw the universe not as chaos, but as kosmos—ordered, patterned, intelligible. Pythagoras famously said, “All is number,” not in a reductionist way, but as a recognition that beneath all things lies an order we can perceive. Plato’s Timaeus describes the world-soul being formed according to mathematical ratios. Number, for them, was not mere calculation—it was a path to the contemplation of reality as parts and whole.

The Church Fathers and medieval scholars received this vision and baptized it. They saw in the Quadrivium a ladder ascending from earthly observation to divine contemplation and back again to a transformative vision for how life ought to be. Boethius, the Roman Christian philosopher, wrote that mathematics “leads the mind upward from sensible things to eternal realities.” It trains us to see the connections between the concrete and abstract.

Thus, each discipline of the Quadrivium reflects a different aspect of number:

1. Arithmetic is number in itself—pure, abstract, eternal. It reflects the divine unity and simplicity of God. The number one represents unity; three, the Trinity; seven, completeness. Numbers are not merely tools, but symbols, adjectives of reality, icons through which we discern the mind of the Maker.

2. Geometry is number in space. It concerns the measurement and relation of shapes and distances. From Euclid to cathedrals, geometry taught the ancients and the medievals that proportion and symmetry are beautiful—and all beauty is a stream flowing from the divine, who is eternal and infinite beauty.

3. Music is number in time. The movement of tones and rhythms according to measure reveals hidden laws of harmony. For Boethius, there were three types of music: musica mundana (the music of the cosmos), musica humana (the harmony of body and soul), and musica instrumentalis (the music we hear). Music, rightly understood, aligns our souls with the order of God’s world because its beauty is enstoried proportionality. Musica Instrumentalis produces Musica Humana by reflecting Musica mundana.

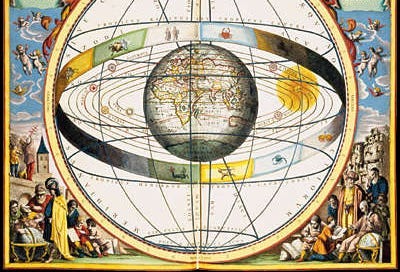

4. Astronomy is number in space and time. It tracks the dance of the heavens. The medieval mind saw in the stars not only objects of scientific curiosity but messengers of divine grandeur. Psalm 19 proclaims, “The heavens declare the glory of God.” By studying, enumerating, and measuring the proportions of the movements of the stars, ancient astronomers sought not just prediction, but understanding—wisdom rooted in wonder. They saw in the measured consistency a model for rulers, a model for worshippers, and a liturgy of a creation overflowing with love for its creator.

Together, these disciplines formed the foundation of imaginative reasoning. In the medieval university the quadrivium were not ends in themselves. They were preparatory for the study of philosophy and theology. They trained the mind to think with clarity and reverence, to see in creation the fingerprints of the Creator. Thomas Aquinas, synthesizing Aristotle and Augustine, taught that these arts were servants of sacred doctrine. They trained the imagination on careful multi-dimensional reasoning, from concrete to abstract and back again,

The Quadrivium, then, is not obsolete. It is a discipline of attention, training us to perceive the patterned glory of God’s world. It offers more than knowledge—it fosters wisdom, the harmony of truth and love. In an age of fragmentation and noise, the Quadrivium calls us back to order, beauty, and wonder.

The end of Christian learning is not merely to master facts, but to be mastered by the truth that sets us free. The Quadrivium is a path. An overgrown and forgotten path, but still an effulgent and joy-filled path, toward that truth.

I'm curious if you read my response to this (I sent you a DM, but not sure if you've seen it)--I would really love to interact with you on this. There are a multitude of errors that the classical christian movement has made about the quadrivium (all of which are very understandable, it is very difficult to read the tradition). As one who was educated in the classical ed world and is now a teacher at a classical school, I really want to see that change.

Beautiful and helpful summary.