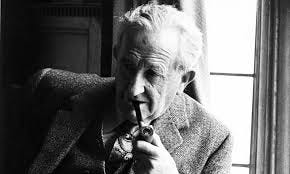

The idea of “true myth” was central to J.R.R. Tolkien’s understanding of how the Gospel relates to imagination. The term captures the paradoxical claim that Christianity is both a myth and a fact—a story that fulfills the longings expressed in ancient myths, but also one that uniquely and historically happened. Tolkien explained it to Lewis in 1931, where he explained that the Gospel is “the Myth that really happened,” giving Lewis the categories that he needed to be able to finally walk away from atheism

In traditional myths—from Norse sagas to Greek epics—human beings told stories of dying and rising gods, heroic quests, battles with evil, and paradisiacal restoration. The Modernist take, that these are lies people told to chain the chaos (or one another) is deeply unsatisfying. Modern man has proven mankind’s inability to live without a mythos. We jettisoned the old God only to find that the new gods of the 20th century demanded more blood than all the other centuries combined.The old myths were not seen by Tolkien as lies but as vessels for profound truths about the world, the self, and the divine life. Tolkien and Lewis believed that these myths expressed real desires—longings for beauty, justice, immortality, and home—that naturalism could not explain away by. Myths point to something deeper than mere facts alone: it speaks to meaning and purpose.

In the Incarnation, Tolkien saw, myth and fact unite. The longings expressed through poetic myth—the hope of victory over death, the yearning for reconciliation, the coming of a savior—are fulfilled in the real-life death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In Christ, the pattern of the myth, the symbolic reality, becomes historic reality: not merely a symbolic death, but a crucifixion; not only a metaphorical resurrection, but an empty tomb. Thus, Christianity is the true myth: it has the narrative beauty and archetypal power of the old myths, but also the grounding in time, space, and history that myths lacked.

This theme is deeply embedded in Tolkien’s own storytelling. Though The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory, it is suffused with mythic patterns that echo the True Myth—sacrificial love, Gandalf’s fall into heart of the earth, the paths of the dead being the way to victory, the hope of a king returning. For Tolkien, such stories do not compete with the Gospel but prepare the heart for it. They baptize the imagination, so that when the true story is heard, it is recognized not as a foreign intrusion but as the fulfillment of all our deepest stories.

In this way, Tolkien’s idea of “true myth” bridges faith and imagination. It affirms that our desire for stories is not a distraction from truth but a God-given hunger for it. The Gospel is not the end of storytelling, but its consummation—the place where the Author of all becomes a character in His own tale, and where joy enters the world not only through the telling, but through the happening.

I wonder about this in terms of new religions being formed after the 1st century. I haven't done too deep of a dive but the new religions all seem to fall under either 1. A revival of old religion (like Mythras cult) - until it dies because of Christianity, or 2. it revives an old hindi/bhuddist idea because Christianity had not arrived there yet, or 3. It creates a subversion of the Christian story - islam, mormons, etc...

I have no idea how to prove this theory tho!

This is absolutely correct! And should be understood in light of the scriptural teaching about the light coming into the people who live in darkness. What was that light that the pagans were expecting to see and how did they know to look for it? A lot of my work on the YouTube side of things is trying to get modern pagans to understand why it is that our Pagan ancestors so freely submitted to the powerful preaching of Patrick in his day